An international collaboration including researchers from TRIUMF and the U.S. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has refined a key process in understanding extreme plasmas such as those found in the sun, stars, at the rims of black holes and galaxy clusters. In short, the team identified a new solution to an astrophysical phenomenon through a series of laser experiments.

In the new research, appearing in the Dec. 13, 2012, edition of the journal Nature, scientists looked at highly charged iron using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) free-electron laser. Highly charged iron produces some of the brightest X-ray emission lines from hot astrophysical objects, including galaxy clusters, stellar cornea, and the emission of the Sun.

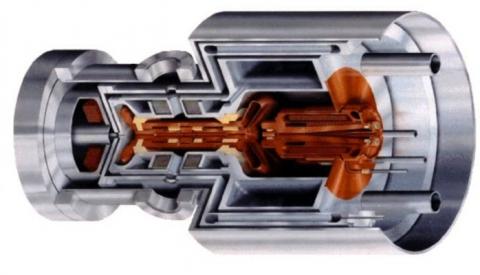

The primary experimental tools were (a) the Linac Coherent Light Source at the U.S. SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and (b) an electron beam ion trap (EBIT) built in collaboration with the University of Heidelberg in Germany. An EBIT is used at TRIUMF in the TITAN experiment.

The experiment helped scientists understand why observations from orbiting X-ray telescopes do not match theoretical predictions, and paves the way for future X-ray astrophysics research using free-electron lasers such as LCLS. LCLS allows scientists to use an X-ray laser to measure atomic processes in extreme plasmas in a fully controlled way for the first time. The highly charged iron spectrum doesn't fit into even the best astrophysical models. The intensity of the strongest iron line is generally weaker than predicted. Hence, an ongoing controversy has emerged whether this discrepancy is caused by incomplete modeling of the plasma environment or by shortcomings in the treatment of the underlying atomic physics.

"Our measurements suggest that the poor agreement is rooted in the quality of the underlying atomic wave functions rather than in insufficient modeling of collision processes," said Peter Beiersdorfer, a physicist at Lawrence Livermore and one of the initiators of the project.

Many astrophysical objects emit X-rays, produced by highly charged particles in superhot gases or other extreme environments. To model and analyze the intense forces and conditions that cause those emissions, scientists use a combination of computer simulations and observations from space telescopes, such as NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton. But direct measurements of those conditions are hard to come by.

In the LCLS experiments, the focus was on plus-16 iron ions, a supercharged form of iron. The iron ions were created and captured using a device known as an electron beam ion trap, or EBIT. Once captured, their properties were probed and measured using the high-precision, ultra brilliant LCLS X-ray laser.

Some collaborators in the experiments have already begun working on new calculations to improve the atomic-scale astrophysical models, while others analyze data from followup experiments conducted at LCLS in April. If they succeed, LCLS may see an increase in experiments related to astrophysics.

"Almost everything we know in astrophysics comes from spectroscopy," said team member Maurice Leutenegger, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, who participated in the study. Spectroscopy is used to measure and study X-rays and other energy signatures, and the LCLS results are valuable in a "wide variety of astrophysical contexts," he said.

The EBIT instrument used in the experiments was developed at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics and will be available to the entire community of scientists doing research at the LCLS. Livermore and TRIUMF have been pioneerd in EBITs. Various EBIT devices have been operational at LLNL for more than 25 years. This was the first time that an EBIT was coupled to an X-ray laser, opening up an entirely new venue for astrophysics research, according to Beiersdorfer.

TRIUMF's Martin Simon from the TITAN experiment was a co-author on the paper.

Researchers from SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory; the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg, Germany; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center; the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science; GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research; and Giessen, Bochum, Erlangen-Nuremberg and Heidelberg universities in Germany; Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at SLAC; and TRIUMF in Canada also collaborated in the LCLS experiments.

-- from a U.S. DOE press release