Last week's announcement about the discovery of a new particle at CERN's LHC experiment took the world by storm. Across the traditional press, social media, and on street corners and around water coolers, everybody was talking about Higgs particles, molasses, mass, and electroweak symmetry-breaking.

What happened?

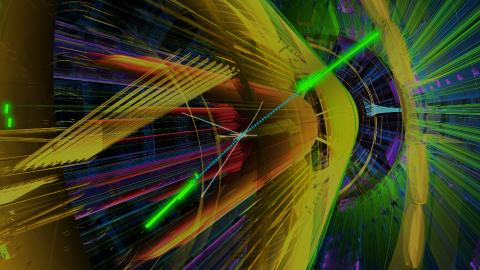

So what actually took place in the early hours of July 4? The two major particle-physics experiments at CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Geneva, Switzerland, announced the discovery of a new particle—one that appeared to behave just like the fabled but not-yet-found Higgs boson. Not only did both experiments observe convincing evidence of the existence of a new particle, but also the evidence they found was corroborating: it seemed obvious that both independent experiments were observing the same phenomenon in nature.

The result? A news story that travelled 'round the world at nearly light speed and occupied TVs, mobile-phone screens, radios, newspapers, and magazines everywhere.

For those who want to master the conceptual understanding of the Higgs particle and the role it plays in particle physics, consider Daniel Whiteson's animated lesson.

Why did it happen?

How did the world get so enthusiastic about this breakthrough? Well, there were probably two contributing factors. (1) The intrinsic curiosity of human beings about how the world works, and (2) The Higgs-particle search as a quest.

Ever since humans first came out of caves at night and looked at the sky and wondered what made the stars shine, we have been curious as a species about the universe. Particle physics, just as sciences like astronomy and cosmology and microbiology do, strives to address this fundamental curiosity. What are the fundamental building blocks? How do they interact? Can we understand the human experience as a deductive sequence from basic principles of atoms and their interactions? So far, we don't have the answer to that final question. But the Higgs boson does validate a fundamental description of reality that we call the Standard Model.

The "God particle?" Really? Laying aside the specious history of who first labeled the Higgs particle with this term (a book publisher!), physicists do think of the Higgs boson as a keystone in the modern model of what is happening at the most elementary levels in the universe. Particle interactions with the Higgs field is what provides the experience of mass, and excitations of that fundamental field are what constitute the Higgs boson itself. For the past decade, if not longer, particle physicists have consistently referred to this quest of "understanding the origin of mass" as a sacred quest. In this sense, the discovery of a particle that appears to be the Higgs boson is a big deal: it is the fulfillment of at least one man's work (Peter Higgs) as well as the culmination of effort from thousands of individuals from all around the globe as well as the European treaty organization CERN. That is pretty exciting!

How did we (Canada) end up here?

So what did Canada do to be a part of this exciting breakthrough? Were we just in the right place at the right time?

Well, no. Canada has been a critical element of everything that led up to this breakthrough—and in what's next. For more than a decade, Canadian scientists and students have been working away in universities, airport lounges, coffee shops, universities, and TRIUMF to design, build, and then operate the world's largest science project: the Large Hadron Collider at CERN and the ATLAS detector. Canadian involvement has taken sustained, intentional investment from the Government of Canada. As recent as 2010, the Government has had to consider whether addressing the basic quest of what makes the universe tick is an important part of spending of the Canadian taxpayer's dollars. Fortunately, they judged the public's view as YES.

Consider that Professor Michele Lefebvre (UVic) was the first Canadian who wrote a successful grant proposal for Canadians to join the LHC activities. Alan Astbury (also of UVic and then director of TRIUMF) took the giant step to directly enlist TRIUMF as a core contributor to the accelerator. With strong support from the Government of Canada via funding to TRIUMF through a contribution agreement from National Research Council Canada, the large accelerator construction effort was highly successful. Engineering physicists Ewart Blackmore from TRIUMF was the key steward of this effort.

After that, subsequent TRIUMF director Alan Shotter (UAlberta) worked with Simon Fraser University to secure enthusiasm and support for the Canadian ATLAS Tier-1 Data Centre (funded by CFI and the Government of British Columbia) as a national project from 10 universities. The project was led by Professor Michel Vetterli (SFU and TRIUMF). Finally, the ATLAS-Canada detector elements (with funding by NSERC) were constructed over several years under the leadership of Professor Robert Orr from the University of Toronto, which ultimately led to the Canadian pieces of the detector we have sitting in Geneva, Switzerland. The calorimeter, which was important to the Higgs discovery, was built by a team at TRIUMF led by Chris Oram, a TRIUMF scientist.

The point is that many students, professors, university administrators, government bureaucrats, and elected officials—year after year—had to believe in the promise of the project to make it successful. In the U.S., a competing project called the Superconducting Supercollider (SSC) that was also aimed at uncovering the Higgs was eventually cancelled. The world community quickly coalesced around the LHC activities at CERN—which proved up to the challenge.

Nigel S. Lockyer, director of TRIUMF, commented, "TRIUMF, and Canada, are part of this discovery because of the steadfast support of basic discovery science over the years all the way from the individual citizens, the high-school science teachers, up to the Prime Minister. Canada is part of the forefronts of science, and it would never happen without the whole spectrum of enthusiasm, support, and encouragement." As Canada's national laboratory for particle and nuclear physics and point institution for the pan-Canadian Higgs effort, TRIUMF has been deluged with inquiries, public comment, and media requests. Lockyer noted that his favourite conversations have been with the local construction workers, administrative staff, students visiting the laboratory, and senior officials in the government: "They're all just amazed, satisfied, and thrilled that we did this. We're all intrigued by, interested in, and supportive of science."

What makes us perhaps the most proud, though, is that this breakthrough is a victory not just for science, but for humanity. It took scientists from more than 137 countries, from Israel and Palestine, from India and Pakistan, from the U.S. and Brazil and Mexico, from Asia and Europe and Russia and Africa.

Together, we are stronger; together we persevere in our quest to understand; together, we transcend our differences and dedicate ourselves to a shared future.

-- by T.I. Meyer, TRIUMF's Head of Strategic Planning & Communication, and Nigel S. Lockyer, TRIUMF's Director