The TRIUMF colloquium on October 27 at the National Research Council Canada generated a lot of buzz at the laboratory. Many in the audience were curious about how TRIUMF’s physics research helps doctors understand the human body. The story behind how our bodies work—and in particular, the brain—is incredibly complex, and there is still a lot about body and brain interaction that we do not understand. The mere act of measuring what happens in the brain comes with a myriad of challenges. How do you examine the biochemical inner workings of the brain without cutting it open? A packed room of TRIUMF’s top scientists attended the colloquium to gain insight into that very question.

And there are few people more qualified to give that insight than Dr. Yu-Shin Ding, an internationally recognized Professor of Diagnostic Radiology from Yale University. Her colloquium, Imaging the Functioning Human Brain with Positron Emission Tomography (PET), covered her extensive work to understand biochemical transformation and movement of drugs in the living body using radiotracers. Yu-Shin’s interdisciplinary background, which bridges chemistry, biology, pharmacology, and even math, allows her to provide a uniquely holistic perspective on the brain. The excitement around her colloquium revealed the interest at TRIUMF around her work. Yu-Shin is currently working at TRIUMF during a six-month sabbatical from July to December.

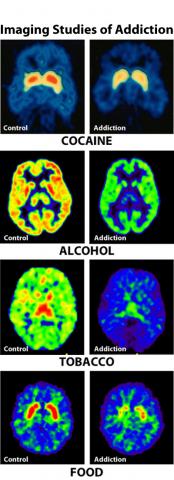

Yu-Shin’s expertise is in PET imaging, a radiopharmaceutical technique for producing a three-dimensional image of metabolic activity inside the body. The system traces gamma rays emitted from radioactive isotope tracers that are attached to a specific, biological target molecule, such as dopamine or norepinephrine, thus allowing a visualization of how the molecule interacts and metabolizes inside the body. By comparing images from different patients, doctors can better understand what actually happens to the brain when a patient develops Parkinson’s disease, becomes addicted to cocaine, or takes Ritalin for ADHD.

Yu-Shin’s experience in the field is extensive. At Yale, she serves as the Director of PET Radiochemistry Research & Development, and the Co-Director of the Yale PET Centre. Previously, she was the Head of Radiotracer Development at the Translational Imaging Center at Brookhaven National Laboratory in the US, where she contributed to the development of various tracers needed for medical imaging. Much of her work has been on neurotransmitters like dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, glutamate, and acetylcholine. Neurotransmitters are critical biochemicals that facilitate brain function. Scientists want to better understand their role in mental health, addiction, depression, ADHD, and neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.

TRIUMF’s nuclear medicine division is especially delighted to host Yu-Shin. One of the main goals of the six-month collaboration was to learn to develop methylreboxetine (MRB) at TRIUMF, a tracer that will allow scientists to study the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. TRIUMF has not had this capability in the past, so this technology opens the door to new projects and further research. Ultimately, the hope is to use MRB in studies of Parkinson’s disease at the UBC hospital, a lead partner in the project.

TRIUMF came to Yu-Shin’s attention when she was on the Life Sciences Projects Evaluation Committee (LSPEC), an advisory board that both reviews new research proposals for feasibility and reports on the progress of ongoing projects. TRIUMF senior scientist and international expert in radiochemistry Tom Ruth describes Yu-Shin Ding’s participation in the project as “a win-win for everybody,” a good example of how those who review TRIUMF have gained interest and become participants.

Yu-Shin herself was excited to come to TRIUMF. She says she feels an attachment to the site because as Canada’s national physics laboratory, it resembles Brookhaven, the American equivalent where she worked for over fifteen years. The national laboratories “have a certain kind of environment…a spirit of doing research,” according to Yu-Shin, “I like TRIUMF very much.”

Yu-Shin’s current work at TRIUMF, developing the MRB tracer for the norepinephrine transporter (NET), is ground-breaking. There has been no study to date that has done imaging of NET in humans, because no tracer for it existed. However, NET plays an important role in many disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, substance abuse, and ADHD.

Yu-Shin says she strives to get “the complete story” on serious disorders. It is this holistic and comprehensive approach that sets her apart. In the brain, there are three main monoamine neurotransmitter systems: dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. The three systems work in tandem, but are often studied in isolation. As a result, there is only a partial understanding of the story, leaving the potential for negative consequences.

Methylphenidate, or Ritalin, is a drug commonly used to treat ADHD. Patients, mostly children, may take Ritalin pills three times a day. Doctors know that the therapeutic effect of the drug may be related to the dopamine system, but the effect on the norepinephrine system is unknown. Yu-Shin addressed the issue in a paper published last year, demonstrating that, in fact, methylphenidate affects the norepinephrine system even more than the dopamine system. Scientists don’t know in detail what this effect may lead to; the answer to this question lies in further PET studies to determine the complete story.

Her work also examines the connection between the brain and the body, two entities that in nature are inextricable, but are too often studied in isolation. Without looking at all our body’s systems and how they interact, a full understanding of disease and how to treat it is impossible.

This perspective is reflected in Yu-Shin’s background of integrated science. Typically, chemists stay within their field, and imaging specialists stay within theirs. Yu-Shin, however, bridges medicine with chemistry, biology, pharmacology, and even some kinetic modeling. She is involved with the entire process, from developing and testing tracers, to characterizing new probes in preclinical models, to clinical studies in humans. “PET is multidisciplinary,” says Yu-Shin, and so this approach allows her to “get an understanding of the whole picture.”

Yu-Shin’s interest in PET technology and its multidisciplinary nature was sparked in her last year of schooling, when she attended a seminar by PET pioneers Alfred Wolf and Joanna Fowler. “I was just fascinated,” she recounted, “[it was] like a trigger to make me think, ‘This is something I’d like to do, to bridge chemistry with human study.’"

Back at the crowded colloquium where TRIUMF’s top scientists hope to learn more about PET research, Yu-Shin offers glimpses of the potential medical advances that may result from the increased PET research at TRIUMF made possible by her contributions of specialized tracers. The new MRB tracer will soon help doctors articulate the effect of Parkinson’s disease, or ADHD on NET. Will it provide us with as much insight on Parkinson’s disease as PET studies on addiction or depression have done?

TRIUMF is currently in the process of having the MRB tracer approved for trials in humans. The next steps will involve sampling for a reliable patient population. Moving forward, Yu-Shin has already started on developing a tracer for serotonin at TRIUMF. The goal is to have tracers ready for each of the three neurotransmitter systems in the brain, giving our scientists a comprehensive overview of brain function.

Thanks to Yu-Shin and her incredible efforts and experience, TRIUMF has become even stronger as a prominent player in the field of nuclear medicine. Her expertise, coupled with the strong research program offered at TRIUMF and at UBC, will benefit many in the future; in short, this collaboration is incredibly productive. While the human body is extraordinarily complex, Yu-Shin’s contributions are leading us to a better understanding of the complete story of the human body.

-- by Aaron Lao, Communications Assistant